I’m a climate realist. My assessment of the science indicates the climate is changing but humans are responsible for at most only a small amount of global climate changes. In addition, the data shows the climate shifts that have occurred up until now have been largely beneficial, contributing to a widespread greening of the earth, increased crop production, and, as nutritious food supplies increase, a decline in malnutrition and a general improvement in human health. Also, the best economic analyses indicate that even if humans are contributing to climate change, radical policies like the Green New Deal (GND) or those that would be necessary to meet the goals of the Paris climate agreement would impose far greater costs and harms on the people of most countries than the supposed climate-induced costs or harm they are intended to prevent.

Interestingly, on the latter point concerning the relative benefits and costs of extreme action to fight climate change, my views largely align with those of prominent economists who disagree with my assessment of the science, who believe human fossil fuel use is responsible for most of the climate change occurring on a global scale.

Nobel Prize-winning economist William D. Nordhaus, Ph.D., is under attack by environmental alarmists despite agreeing with them that humans are driving costly climate changes that should be remedied or reduced, reports American Enterprise Institute Resident Fellow Benjamin Zycher. Nordhaus received the 2018 Nobel Prize in economics largely in recognition of his integrated assessment model of the science and economics of climate policies, a model being used by international bodies and governments to push restrictions on fossil fuel use.

Despite his bona fides as a believer in in large potential dangers of human-caused climate change, Nordhaus is under attack because, like other prominent mainstream economists who’ve toted up the benefits and costs of climate change and actions proposed to prevent it before him, his work shows the sharp, immediate restrictions on fossil fuels proposed by climate alarmists are unrealistic and are likely to cause more harm than good. Nordhaus favors a carbon tax or similar pricing policies to reduce fossil fuel use over time. He even supports the Paris climate agreement, combined with the imposition of tariffs on nations that do not participate in the agreement, or, participating, then fail to reduce emissions by the agreed amounts. Yet this is not enough for climate alarmists, because what Nordhaus doesn’t subscribe to are policies to end the use of all coal, natural gas, and oil in the next 10, 15, or even 25 years. Nordhaus’s assessment of the evidence is that complete decarbonization of the economy, regardless of a nation’s stage of economic development or availability of viable alternative energy sources, is more dangerous than the realistically expected harms from climate change.

Nor is Nordhaus alone among economists in his negative assessment of radical actions to fight climate change. Economist Richard Tol, Ph.D., who has authored dozens of articles and a widely used textbook on climate economics, has written that although climate change seems to be a real problem, it is not the biggest problem in the world, or even the biggest environmental problem. In his textbook, Tol says the probabilities of severe climate events occurring are so unlikely it’s fair to disregard them entirely. Tol says arguments to the contrary—that a climate catastrophe is in the offing—are not based on evidence but rather are “alarmism” generated largely by the self‐interest of select businesses, politicians, and international bureaucrats.

Poor countries with limited adaptation capacity face the greatest threat of marginal harm from climate change, according to Tol, and economic development is best means of addressing those potential harms, because it improves this capacity. Tol also endorses a limited carbon dioxide tax to reduce marginal negative impacts from continued fossil fuel use.

One of the earliest attempts to monetize the benefits and costs of actions to limit supposed human-caused climate change came from the late Stephen Brown, Ph.D., who at the time was a senior economist and assistant vice president of the Federal Reserve Bank in Dallas. Brown conducted a cost-benefit analysis of meeting the greenhouse gas emission reduction targets set in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, a predecessor to the Paris climate agreement. Under the Kyoto Protocol, 36 industrialized countries and the European Union made binding commitments to cut their greenhouse gas emissions the equivalent of an average of 5 per cent below 1990 levels between 2008 and 2012. (In case you are wondering, they badly missed that target.)

Brown acknowledged there were significant scientific uncertainties concerning whether humans were causing dangerous climate change. However, because the potential harms from climate change could be significant, countries would be wise to treat emissions reductions as a form of insurance, Brown wrote. Brown’s analysis indicated the emission reduction targets set in the Kyoto Protocol were far too high, that countries were purchasing far more insurance than they should. Brown estimated the Kyoto treaty would require seven times more carbon dioxide reduction by the United States than was justified by a comparison of costs and benefits, with similar results applying to other developed countries. As a result, Brown suggested the optimal U.S. emission reduction would be just 14 percent of what the Kyoto Protocol required.

I agree with economists like Nordhaus, Tol, and Brown that the extreme policies called for by prominent, powerful climate alarmists, such as presumptive Democrat presidential nominee Joe Biden and running mate Kamala Harris, in which centralized governments impose top-down industrial and commercial policies and dictate individuals’ housing, travelling, and lifestyles to decarbonize the world economy in the next few decades, would be a disaster for most people around the world. For those, like myself, who think alarmists overstate the scientific evidence of a human role in climate change, even the halfway measures endorsed by Nordhaus, Tol, and others are just a slower escalator to hell.

The best climate policies are the best policies in general regardless of concern about climate change: policies that permit markets to provide for continued economic growth in developed countries while allowing for the most rapid economic improvement possible in developing countries. In general, people in wealthier societies are healthier, devote more resources to environmental protection, and are better able to adapt rapidly to and respond to natural disasters and changing climate conditions than are people in poor countries lacking access to relatively inexpensive fossil fuels and the benefits flowing from their use.

— H. Sterling Burnett

SOURCES: National Center for Policy Analysis; American Enterprise Institute; Copenhagen Consensus; Review of Environmental Economics and Policy

IN THIS ISSUE …

NEXT-GENERATION CLIMATE MODELS TOO HOT, GETTING HOTTER … HEAT WAVES SCARCER NOW THAN IN THE PAST … CARBON DIOXIDE INCREASE HAS BEEN GOOD FOR FORESTS

NEXT-GENERATION CLIMATE MODELS TOO HOT, GETTING HOTTER

Numerous peer-reviewed studies have demonstrated the climate models used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to make temperature projections based on a variety of greenhouse gas emission scenarios, have no predictive value. Dozens of models undertaking hundreds of model runs or iterations have consistently overstated the warming the Earth has experienced and, based on experience, the warming we might expect, when compared to temperature data recorded at ground-based measuring stations, by satellites, and by weather balloons.

Ross McKitrick, Ph.D., of the University of Guelph in Canada and John Christy, Ph.D., of the Earth System Science Center at the University of Alabama in Huntsville ran a comparison of recorded temperature data against the temperature projections of the next generation of climate models, the new Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6), models scientists associated with the IPCC are saying are improved and more accurate. The IPCC is relying on CMIP6 models for its forthcoming climate reports.

Using historically measured forcings (greenhouse gas emissions and other factors), McKitrick and Christy compared CMIP6 temperature projections for the period 1979 through 2014 against multiple sets of temperature data recorded by three different systems used to measure temperature and other climate and weather data: (1) four different weather balloon data sets; (2) four different sets of data from various global satellites used to track climate and weather; and (3) four temperature datasets from land-based stations or measuring locations—two from Europe, one from Japan, and one from the United States—covering the same time period.

McKitrick and Christy found the three different types of observational sources of data produced tightly grouped global and regional (the tropics) temperature readings, while the CMIP6 readings were still running hot, with many of the models producing temperature trends even higher, and thus less reflective of actual temperature measurements, than the previous generation of flawed models.

The researchers write, “What was previously a tropical bias is now global. All model runs warmed faster than observations in the lower and mid-troposphere, in the tropics and globally. On average, and in most individual cases, the trend difference is significant.”

The authors conclude the cause of the mistakenly high temperature projections, now, as with past climate models, is the assumption of an “unrealistically high” climate sensitivity—the Earth’s temperature response over time to a set amount of greenhouse gas emissions added to the atmosphere. When modelers assume the climate response of added carbon dioxide to the atmosphere is greater than it is in reality, the models produce too much warming.

The new models confirm, once again, the old adage of “garbage in, garbage out.”

SOURCE: Earth and Space Science

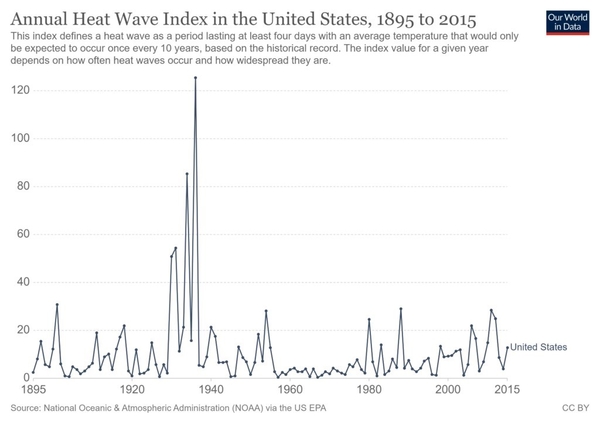

HEAT WAVES SCARCER NOW THAN IN THE PAST

A new summary of the available data conducted by award-winning meteorologist Anthony Watts, a senior fellow at The Heartland Institute, shows heat waves have been far less frequent and severe in recent decades than they were in the past—for instance in the 1930s, nearly 100 years ago.

In Climate at a Glance: U.S. Heatwaves, Watts notes a majority of each state’s all-time high temperature records were set during the first half of the twentieth century. Watts also reports the most accurate nationwide temperature station network, implemented in 2005, shows no sustained increase in daily high temperatures in the United States since at least 2005.

Global warming is not making heat waves worse or producing more record-high temperatures, because the vast majority of the warming the Earth has experienced over the past century occurs during winter, at night, and closer to the poles—producing higher nighttime lows in the most frigid environments instead of higher daytime highs on average across the globe.

As the graph below illustrates, heat waves were much more frequent and severe during the 1930s than in recent years. The data also demonstrate the amount of recent heat waves is well within the historically typical range.

SOURCES: Climate Realism; Climate at a Glance

CARBON DIOXIDE INCREASE HAS BEEN GOOD FOR FORESTS

A recent study published in Ecological Monographs, the official journal of the Ecological Society of America, shows the recent increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations and the accompanying modest increase in global average temperature have substantially increased forest productivity.

More than two-dozen scientists, from 11 different universities and research institutions, examined hundreds of thousands of carbon observations collected over the last quarter-century at the Harvard Forest Long-Term Ecological Research site, one of the most intensively studied forests in the world. Their research revealed “the rate at which carbon is captured from the atmosphere at Harvard Forest nearly doubled between 1992 and 2015,” reports EurekaAlert!.

The scientists found 100-year-old oak trees, trees rebounding from colonial-era land clearing, intensive timber harvest, and the 1938 hurricane, have been growing faster in recent decades, due primarily to increased absorption of carbon dioxide, combined with modestly higher temperatures and a longer growing season. The researchers found carbon dioxide absorption doubled for the recovering oak forests between 1992 and 2015.

“It is remarkable that changes in climate and atmospheric chemistry within our own lifetimes have accelerated the rate at which forests are capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere,” a co-lead author, Professor Adrien Finzi of the Department of Biology at Boston University, told EurekaAlert!.

“Our data show that the growth of trees [and not the soil] is the engine that drives carbon storage in this forest ecosystem,” Audrey Barker Plotkin, a senior ecologist at the Harvard Forest and a co-lead author of the study, told EurekaAlert!.

The authors said they found it encouraging that even as the trees in the Harvard Forest have begun to reach their second century of life, they show no indication their growth rates are slowing.

SOURCES: EurekaAlert!; Ecological Monographs (behind paywall)

The Climate Change Weekly Newsletter has been moved to HeartlandDailyNews.com. Please check there for future updates!