Is the US Constitution hostile to religion? Is the US Constitution hostile to private education provided by sectarian i.e., religious, institutions? Is the US Constitution hostile to parents determining how best to educate their children if the parents consider religion to be a crucial component of the education? Those issues are at issue in the case of Carson v Makin. Oral arguments were held on December 8, 2021.

Let’s begin with the text of the First Amendment to the US Constitution. It says:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peacefully to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Note that the very first right mentioned in the very first Amendment of the Constitution is the right to be free of a State established religion and to practice one’s religion, whatever that may be or even no religion at all, free of government control or restraint. To the Founding Fathers, religious freedom was fundamental to creating a free society. The Founders had come from Britain which had a culture that did not respect religious freedom. The other rights mentioned, also fundamental a free society, had as well roots in the culture in Britain which considered them to be conditional and limited.

The fact that religious freedom was first shows how important the Founding Fathers considered religious freedom to be. Thomas Jefferson, a Virginian, was disturbed by the fact that Virginia, before the Revolution, had an official Church—the Church of England—and dissenters were severely discriminated against and often severely persecuted. As a result of the efforts of Jefferson and others of like mind, Virginia adopted the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. This effort was opposed by many prominent men of that era, including Patrick Henry, Edmund Pendleton, Spencer Roane, John Marshall and Richard Henry Lee.

These gentlemen advocated for a law that would institute church taxes to promote religion. Jefferson, who then was Ambassador to France, together with James Madison and others defeated that effort. Nowhere in the text of the First Amendment or in the writings of Jefferson, Madison and others of the Founding Fathers is there any hint of hostility to religion in general or the right of people freely to practice their religion. In fact, Madison proposed that a bill of rights be adopted that expressly guaranteed religious freedom. Often those who advocate for a very narrow interpretation of the free exercise of religion clause and rely on the establishment clause point to Jefferson writing in 1802 to the Danbury Baptist Association that the establishment clause built a “wall of separation between the church and the state”.

In 1971, in the case of Lemon v Kurtzman, the Supreme Court established a three-prong test for laws dealing with religious establishment. The Court held that to be constitutional, a statute must have “a secular legislative purpose”, it must have principal effects that neither advance nor inhibit religion and it must not foster “an excessive governmental entanglement with religion”. Many Justices, in subsequent decisions, provided additional tests to determine if a statute violated the establishment clause. For example, Justice Sandra Day O’ Connor suggested an endorsement test in the case of Lynch v Donnelly in 1984. Her concern was that a government action should not convey a message to non-adherents that they are outsiders who are not fully free and possessed of the same rights as everyone else.

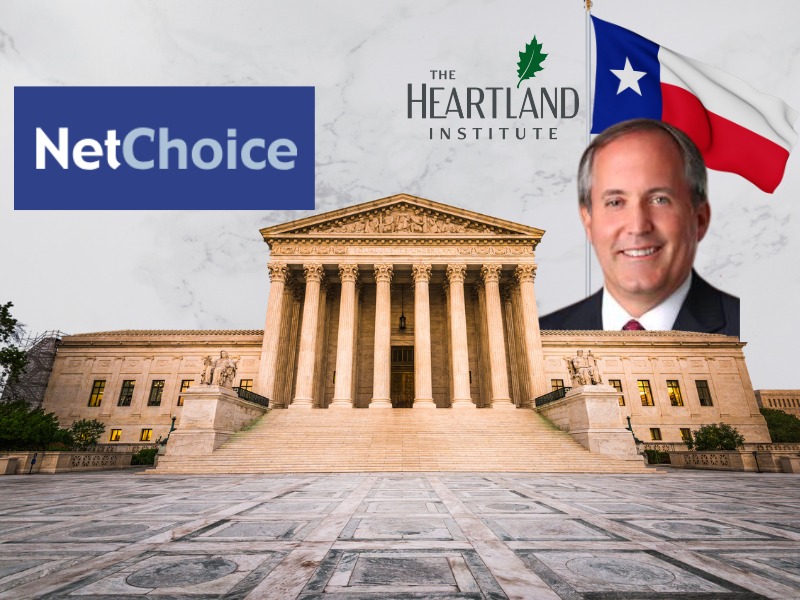

With that background, let’s turn our attention to Carson v Makin. As stated above, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments with respect to this case on December 8, 2021. This case deals with a statute adopted by the State of Maine which provides for tuition grants to all children in Maine to attend any school of their choice other than a school which provides religious instruction. The legislators in Maine recognized that in many rural and sparsely populated areas there were insufficient number of people to support public schools. Most residents in those areas sent their children to private schools, some sectarian and some non-sectarian, and in some cases the schools were far from their residence.

The exclusion of sectarian schools from the use of these tuition grants reflected the desire to avoid the “entanglement” between government and religion but much of the debate in the Maine Legislature reflected an hostility to religious schools, particularly Catholic schools. The “entanglement” argument was, in effect, a convenient shield for this hostility. The exclusion of sectarian schools was challenged as a violation of the free exercise clause of the First Amendment and the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. The Supreme Court had previously held in Espinosa v Montana Department of Revenue that States may not deny sectarian (or parochial) schools the ability to participate in grant programs merely because they are sectarian (or parochial).

In 2015, Montana adopted a statute which provided for dollar for dollar tax credits for individuals who contribute to organizations that provide scholarship money to students attending private schools. The Montana Supreme Court held that the statute violated the Montana Constitution and the US Constitution. The Montana Constitution prohibits any State aid for religious education. The US Supreme Court overruled the decision of the Montana Supreme Court. Justice Roberts in the majority opinion wrote: “The state need not subsidize private education, but once it decides to do so it cannot disqualify some private schools because they are religious.”

However, Roberts made clear that the Court was dealing with the fact that some of the schools benefitted were religious schools and the Court was not dealing with whether the funds provided by the government supported religious instruction. Justices Ginsburg, Breyer and Sotomayor each wrote dissenting opinions. Sotomayor called the decision “perverse”. Justices Thomas, Gorsuch and Alito each wrote concurring opinions. Carson v Makin is now taking on the question not answered in the Montana case— can sectarian schools participate in state grant programs if they provide religious instruction and are not merely sponsored by a religious institution?

It appears from the oral argument that the Supreme Court is about to answer that state grant programs cannot exclude sectarian schools because they provide religious instruction as well as instruction in non- sectarian areas of education. This would be a major victory for advocates of school choice, both advocates that support sectarian schools and advocates who are committed to educational opportunity but are unconcerned about religious instruction. During oral arguments, Justice Roberts raised a hypothetical of two schools, one that teaches its religious beliefs openly and explicitly and teaches a particular set of religious values in the process and the second of which eschews explicit references to God or a holy text and teaches a different set of values motivated by religious beliefs. Roberts asks if one is funded and the other is not, is the state making a distinction “based on doctrine”? Justice Kavanaugh added that it is not enough to say that the state is being neutral because all religious schools are excluded from the program, stating that” discriminating against all religions” is still unlawful discrimination.”

Kavanaugh called for “neutrality” between sectarian and non-sectarian schools. Not surprisingly, the remarks of Roberts and Kavanaugh sent alarm through the organizations that oppose school choice, particularly those that are hostile to religion and religious instruction. The tension between the establishment clause and the free exercise clause of the First Amendment was summed up well by Professor David Strauss of the University of Chicago Law School who said: “We want a principle that says that government shouldn’t be paying the salaries of members of the clergy, But on the other hand, if a fire breaks out in a church, you don’t want the fire department saying, ‘Oh wait a second, it’s a church, we can’t put out the fire’.”

I wonder if the opponents of school tuition assistance that might benefit sectarian schools would say ‘Let it burn’ and if the motivation would be a genuine belief in the “wall of separation” or rather a hostility to religion.